Source: Notices of Brazil, Walsh, 1831

By the late eighteenth century, slavery in the U.S. was a firmly established social, political and economically lucrative institution. It existed in both the North, where slaves were employed in various trades and as skilled laborers, as well as in the South. But with the invention of the cotton gin in 1793, the demand for agricultural labor increased significantly, especially in the Deep South where cotton was the major crop. The cotton gin made cultivation on a huge scale possible, increasing the daily processing capability fifty fold. As a result of increased cotton production and the required labor, the slave population in cottongrowing regions greatly increased.

The economic and political impact of the cotton gin was significant. In South Carolina for example, only the low country-the area south of Charleston including the coastal region-had been able to grow long staple cotton, while the upcountry was only able to grow short staple cotton, which was harder to separate by hand. The invention of the cotton gin made it possible for short staple cotton to be processed as fast as long staple cotton. As a result, the economy of the low country and upcountry became fairly equal. The invention also meant upcountry cotton planters required a large number of workers, so they began importing African slave labor. Though South Carolina’s upcountry now had its own wealthy planter class, the low country still dominated politically since the upcountry received only three-fifths of a vote for every slave.

Europe, which dominated the Atlantic slave trade, began to experience a growing unease with slavery. In the U.S., similar concerns were raised in the North. Led by the Quakers and evangelicals such as William Wilberforce, the anti-slavery movement gained support as opposition to the slave trade increased. Denmark, which had been very active in the slave trade, was the first country to ban it in 1792, though the law went into effect eleven years later. Britain banned slave trade in 1807, imposing stiff fines for any slave found aboard a British ship. That same year the U.S. banned the importation of slaves. Though the British banned slave trafficking, slavery was still legal in the British Empire until 1833.

- In 1773, Phillis Wheatley became the first African American writer to be published in the United States. Her work was cited by abolitionists to refute claims of black intellectual inferiority and to promote educational opportunities for blacks. Born in Senegal, Wheatley’s book Poems on Various Subjects was published two years before the Revolutionary War. Some of her works were published posthumously: Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley (1834) and Letters of Phillis Wheatley, the Negro Slave-Poet of Boston (1864).

- In 1779, London-born John Newton published the first stanza of what would become Amazing Grace, originally titled “Faith’s Review and Expectation,” which drew from his experiences on slave ships. Newton served in the British Royal Navy, but soon began working on slave ships. The experience so transformed him that he experienced a religious conversion, and by 1758 had become a preacher in Liverpool. He became a vicar of a major London church and an abolitionist, and began to write hymns.

- In 1787, free blacks in New York City founded the African Free School. In that same year, Quobna Ottobah Cugoano published Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species. An African abolitionist active in England in the latter half of the eighteenth century, Cugoano was born a Fante, in what is now Ghana. Kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1770, Cugoano was shipped first to the West Indies, but arrived in England in 1772. He actively condemned slavery through participation in the Sons of Africa, an abolitionist group of educated Africans including Olaudah Equiano. As a devout Christian and one of the group’s most vocal members, Cugoano wrote about the history of the slave trade, and argued that European colonialism in the Americas contributed heavily to the issue. He held the British responsible for creating an environment in which slavery could exist and called upon slaves to rebel.

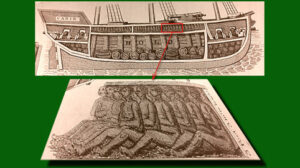

- In 1789, abolitionist Olaudah Equiano, a former slave living in London, a published a widely read autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Equiano was born in Benin and was an Ibo, and like other Africans, was captured by another tribe and became a slave. About six or seven months later, Equiano was brought to the African coast, where he was headed across the Atlantic in the Middle Passage. His autobiography described the conditions on the slave ships in grave detail, from the “shrieks of the women,” and “groans of the dying,’ to the beatings and the envied suicides. When the slave ship arrived in Barbados, Equiano was not bought, and was shipped to Virginia only a few weeks later, eventually sold to Michael Henry Pascal, a lieutenant in the Royal Navy. For the next seven years, as Pascal’s slave, Equiano relocated to England, where he educated himself and traveled on ships under Pascal’s command. After Equiano bought his freedom in 1766 he worked in the West Indies and London. In 1773, he set sail with an expedition to discover the Northwest Passage. Upon return to England, Equiano spoke out against the British slave trade, exposed the cruelty of British slave owners and worked to resettle freed slaves.

- 1793 Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, which made possible large-scale cotton cultivation in the South, thus greatly increasing the need for slaves, whose numbers skyrocketed.

- By 1807, Britain had banned African slave trade, but trafficking by Spanish and Portuguese traders persisted. A modest effort was made to punish those convicted of violating the law, but was rarely enforced and the importation of African slaves continued virtually unabated. The British banned their own ships from engaging in the slave trade, and often attacked the ships of the Spanish, French and Portuguese to put an end to the trade.

Source: 1899 edition of “Democracy in America”

“If there ever are great revolutions there, they will be caused by the presence of the blacks upon American soil. That is to say, it will not be the equality of social conditions but rather their inequality which may give rise thereto.”

– Alexis de Tocqueville

In 1835, Alexis de Tocqueville published Democracy in America from his observations of the American penal system following a French government-sponsored mission to the United States. Tocqueville believed that democracy and equality would replace Europe’s outmoded notions of aristocracy. Upon his return to France, de Tocqueville became a politician and prominent writer during the French Revolution in 1848, and was briefly minister of foreign affairs in 1849.