Source: Wikipedia, Credit: D. W. Griffith, 1915

Beginning in 1896, immigrants from southern and eastern Europe, mainly Italians, Jews and Slavs from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, were the largest groups arriving in the U.S. The reception they received was markedly different from earlier northern European immigrants. They experienced employment and housing discrimination that resulted in many living in urban “ghettos” in the Northeast and the Midwest. Many Americans saw them as “racially” different and inferior. The ideology of race was applied to Southern and Eastern Europeans because they were physically and culturally different from the Northern Europeans and Scandinavians. That racial worldview dominated thinking about human differences and was extended to European populations in the U.S. as well. European intellectuals had begun to see their own populations as divided into races, with attributes that made them unequal.

- In 1879, rumors circulated in African-American communities in the South that Kansas was being set aside for settlement by former slaves. Upwards of 15,000 blacks moved to Kansas; they were called “exodusters” because of their exodus into the dusty Plains state of Kansas.

- Abolitionist Frederick Douglass published The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass in 1881. That same year Joel Chandler Harris published Uncle Remus, a folktale whose characters depicted racial stereotypes.

- In 1881, Helen Hunt Jackson chronicled the federal government’s treatment of Native Americans in A Century of Dishonor.

- In 1883, Mark Twain published Life on the Mississippi; a year later, he published The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, both of which were controversial in their use of racial slurs and depiction of black characters.

- In 1898, the Spanish-American War resulted in the U.S. gaining control over former Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific. As a result of the war, Cuba won its independence in 1902; the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam became U.S. protectorates. There is some debate as to how much propaganda influenced the war. In the 1890s, competing over readership, William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer tried to use their New York City newspapers to sway public opinion about the war with Spain. The first propaganda film, Tearing Down the Spanish Flag, was produced in 1898 in order to inspire patriotism in America and hatred for the Spanish. The film depicted the removal of the Spanish national flag and its replacement with the U.S. flag.

- In 1899, Charles Chesnutt published The Conjure Woman and The Wife of His Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line, some of the earliest fiction that would deal with the “tragic mulatto” theme.

- W.E.B.Du Bois invited African-American leaders to a conference on political action and individual rights in Niagara Falls in 1905 and for several years thereafter. The members of the Niagara Movement, as it came to be known, ultimately formed the NAACP in 1909.

- In 1911, a fire broke out in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, killing 146 mostly immigrant women and girls. The tragedy exposed unsafe working conditions endured by newly arrived European immigrants.

- In 1915, Leo Frank, a Jew, was convicted of murdering Mary Phagan; he was lynched in Marietta, Georgia, amid a climate of anti-Semitism.

- D. W. Griffith released Birth of a Nation in 1915, inspiring the NAACP to publish a 47-page pamphlet titled ‘Fighting a Vicious Film: Protest Against The Birth of a Nation.” The pamphlet called the film as “three miles of filth.” Reviews in The Crisis written by W.E.B. Du Bois were scathing, which instigated a heated debate among the National Board of Censorship of Motion Pictures about whether the film should be shown in New York. However, when President Woodrow Wilson viewed the film at the White House, he proclaimed it not only historically accurate, but “history writ with lightning.” Massive race riots flared throughout the country following the release of the film, peaking in 1919. The blame has been placed, in part, on Griffith’s film by some historians.

- In World War more than two million Americans volunteered and almost three million were drafted. More than 350,000 African Americans served in segregated units. During the war, hundreds of thousands of blacks migrated North to work in factories that geared up for the war.

- In 1917, 40 blacks and eight whites were killed in race riots in East St. Louis, Illinois, sparked by white resentment of blacks working in wartime jobs.

- In 1919, in what became known as “Red Summer,” race riots broke out in Chicago, Washington, D.C. and throughout the South, triggered by large-scale migration North and black employment opportunity during the war.

- In the 1921 Tulsa race riots, Oklahoma whites killed at least 300 blacks and burned 1,400 homes and businesses in the Greenwood section of the city, known as the black Wall Street, after unfounded rumors that a black man had assaulted a white woman. Many also attribute the riots to white resentment of the success of local black businesses.

- Alain Locke published The New Negro in 1925, the first sociological study of contemporary black life.

- The Klu Klux Klan reached its peak in 1925 with an estimated 4,000,000 members, but declined to 30,000 by the 1930s after the conviction of Klan leader, David C. Stephenson in 1925, for second-degree murder.

- The Jazz Singer, starring Broadway star Al Jolson in blackface, opened as the first talking motion picture in 1927. The movie continued the long tradition of black minstrelsy that began roughly a century before.

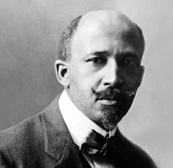

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, created by Cornelius M. Battey, 1919

“The problem of the 20th Century is the problem of the color-line.”

– W. E. B. Du Bois

By the end of the 19th century, AfricanAmerican scholars began to tackle the denigrated images of blacks that dominated the U.S. Perhaps the most prominent advocate for “Negro uplift” was William Edward Burghardt Du Bois. In the first half of the twentieth century, W.E.B. Du Bois was arguably the most prominent activist on behalf of blacks. A contemporary of educator Booker T. Washington, Du Bois took issue with Washington’ acceptance of segregation and political disenfranchisement. Though Du Bois consistently argued against racial inequality, he nevertheless subscribed to elitist hereditarian views. In a collection entitled The Negro Problem, he wrote that the “talented tenth” of African Americans should be encouraged to have children, as a way of improving” the race. Du Bois argued that racialism was the philosophical belief that differences between the races existed biological, social and psychological. He asserted that racism involved using those beliefs to advance the idea that one race was superior to all others, and distinguished between the “conditions” of racism and “racism” itself.