Credit: The Andrew J. Russell Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

In 1865, the Union Pacific Railroad began laying track, progressing about one mile per day westward. Chinese workers, employed by the Central Pacific in California, provided the labor to push through the mountains. When the two lines were joined in 1869, the Golden Spike was driven at Promontory Point, Utah, completing the Transcontinental Railroad. In 1870, the Union Pacific in Wyoming hired Chinese laborers for $32.50 a month rather than pay $52.00 a month to whites. This kind of treatment caused white laborers in the West to feel that Chinese immigrants were competing unfairly for jobs, which not surprisingly led to years of violent conflict and labor unrest.

- A Senate commission met with Red Cloud and other Lakota chiefs in 1875 to negotiate legal access to the Black Hills of the Dakotas for miners involved in the gold rush; an offer was put on the table to buy the land for $6 million. The Lakota, however, had no desire to alter the terms of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, and when they declared that they would protect their lands from intruders, the Lakota War broke out. The following year, when the government ordered the Lakota chiefs to report to their reservations by January 31, Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and others refused. The army then tried to drive Sitting Bull and the other chiefs onto the reservation through a combined assault, but on June 17, Crazy Horse and 500 warriors surprised U.S. troops on the Rosebud River, forcing them to retreat. When George Armstrong Custer discovered Sitting Bull’s encampment on the Little Bighorn River on June 25th, he charged the village, only to discover that he was outnumbered four-to-one. The Lakota warriors overwhelmed his troops, killing them all, in the battle that came to be known as Custer’s Last Stand. When the news of the massacre emerged, a shocked nation flooded the region with troops, forcing the Lakota to surrender. Only Sitting Bull escaped capture, leading a group of warriors to the safety of

Canada. - In 1878, a group of Northern Cheyenne escaped from their reservation in Oklahoma, trying to reach their lands in the Montana territory.

- Bowing to public pressure, the U.S. government opened land promised to American Indian tribes to white settlers in the first Oklahoma “land rush” in 1889. The tribes received about $4 million for 1.92 million acres.

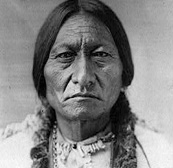

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

“He was not the bloodthirsty man reports from the prairies made him out to be. He asked for nothing but justice…”

– Canadian Mountie James Walsh, upon hearing of Sitting Bull’s death

Sitting Bull, a Native medicine man and a chief of the Lakota, led 1,200 warriors against the U.S. Cavalry at the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876. After the battle, Sitting Bull led his tribe to Canada where they lived until 1881, when he and his followers surrendered to U.S. troops. Though he briefly toured with Buffalo Bill, when asked to address the crowd, he frequently cursed them in his native Lakota language. Toward the end of his life, Sitting Bull was drawn to the ghost dance religion. Because of that, Indian police were sent to arrest him. In the ensuing fight, Sitting Bull and his son Crow Foot were killed.