Courtesy Michael Blakey

By the 19th century, the scientific debate focused on whether human biological difference was just a racial variation, or represented an entirely different species. The “species” theory, polygenism, held that human “races” were of different lineages and suggested a hierarchy outlined in the “Chain of Being” that positioned Africans between man and lower primates.

Polygenism was the antithesis of monogenism, which espoused a single origin theory of humanity consistent with the Bible. Ironically, proponents of slavery were, for the most part, monogenists, because polygenypre-evolutionary scientific argument that human biological "races" are separate species, each descended from different biblical... More was incompatible with the Bible.

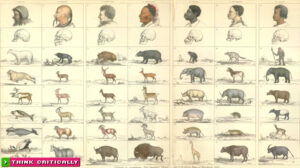

Naturalist Charles Pickering was the librarian and a curator of the Academy of Natural Sciences. In 1843, he traveled to Africa and India to research human races. In 1848, Pickering published Races of Man and Their Geographical Distribution, which enumerated eleven races.

- In the 1820s and 30s, a Philadelphia physician named Samuel G. Morton collected and measured hundreds of human skulls in order to confirm that there were differences among the racesin particular, a difference in brain size. His systematic large-scale experiments made him a pioneer of American racea recent idea created by western Europeans following exploration across the world to account for... More science and physical anthropologythe study of the non-cultural, or biological, aspects of humans and our fossil ancestors. Physical... More. Morton was a proponent of polygenism, which theorized that the different races were different species, with separate origins. Morton amassed a large collection of human skulls from all around the world. He believed he could identify any skull’s racial origin simply by measuring it, and developed tables based on his experiments, which involved pouring lead pellets into skull cavities. Morton assigned the highest brain capacity to Europeans-with the English highest of all. Second was the Chinese, third was Southeast Asians and Polynesians, fourth was American Indians, and the smallest brain capacity was assigned to Africans and Australian aborigines. The collection of skulls is now in the museum of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences. He wrote Crania Americana (1839), An Inquiry into the Distinctive Characteristics of the Aboriginal Race of America and Catalogue of Skulls of Man (1840), and Crania Egyptica (1844). Although Morton was a scientist, he used his influence to make the case for black inferiority to bolster U.S. Secretary of State John Calhoun’s efforts to negotiate the annexation of Texas as a slave state. Calhoun was a pro-slavery advocate from South Carolina.

- In 1854, Josiah Clark Nott published his racial theories in a book of essays written with George Robins Gliddon, an Egyptologist and follower of Samuel George Morton, entitled Types of Mankind or Ethnological Research. It popularized the polygenist theory. In 1856, Nott and Confederate propagandist Henry Hotze translated Arthur Gobineau’s 1853 essay on racial inequality, but with significant omissions and distortions.

- In the wake of Types of Mankind, abolitionists and for the first time, African American scholars, engaged in the race science debate. In the political discourse leading up to the Civil War, prominent statesman and abolitionist Frederick Douglass challenged the leading theorists of the American School of AnthropologyThe study of humans and their cultures, both past and present. The field of anthropology... More, which included Nott, Gliddon, Agassiz and Morton, among others. Work by early “race scientists” tried to prove that blacks were not the same species as whites, and alleged that the rulers of ancient Egypt were not Africans. In Douglass’ 1854 address, “The Claims of the Negro Ethnologically Considered,” he argued that “by making the enslaved a character fit only for slaveryan extreme form of human oppression whereby an individual may "own" another person and the... More, [slaveowners] excuse themselves for refusing to make the slave a freeman…”

Drawing courtesy History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries

“I experienced pity at the sight of this degraded and degenerate race..”

– Louis Agassiz

French naturalist George Louis de Buffon published Histoire naturelle (Natural History) in 1749. Buffon theorized that African skin tone was a result of the intense tropical sun. In Natural History, he also considered the similarities between humans and apes and the possibility of a common ancestry. Perhaps his most significant contribution to the race debate was in recognizing the interfertility of different races. Interfertility undermined the polygenist theory that each race was a different species, since interracial offspring would have been impossible under polygenism.