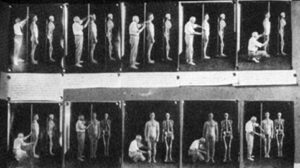

Source: Wikipedia, Credit: Harry H. Laughlin, The Second International Exhibition of Eugenics

The worldwide Eugenics movement gained strength in the U.S. at the end of the 1890s, when theories of selective breeding espoused by British anthropologist Francis Galton and his protégé Karl Pearson, gained currency. Connecticut was the first of many states, beginning in 1896, to pass marriage laws with eugenic provisions, prohibiting anyone who was “epileptic, imbecile or feeble-minded” from marrying. The noted American biologist, Charles Davenport, became the director of biological research at a station in Cold Spring Harbor in New York in 1898. Six years later the Carnegie Institute provided the funding for Davenport to create the Station for Experimental Evolution. Then, in 1910, Davenport and Harry H. Laughlin took advantage of their positions at the Eugenics Record Office to promote eugenics.

Madison Grant, a lawyer known more as a conservationist and eugenist created the “racialist movement” in America advocating the extermination of “undesirables” and certain “race types” from the human gene pool. He played a critical role in restrictive U.S. immigration policy and anti-miscegenation laws. His work provided the justification for Nazi policies of forced sterilization and euthanasia. He wrote two of the seminal works of American racialism: The Passing of the Great Race (1916) and The Conquest of a Continent (1933). The Passing of the Great Race gained immediate popular success and established Grant as an authority in anthropology, and laid the groundwork for his research in eugenics.

A major influence on the eugenics movement was Herbert Spencer, an English philosopher and prominent political theorist. He is best known as the father of social Darwinism, a school of thought that applied the evolutionist theory of “survival of the fittest”-a phrase coined by Spencer-to human societies.

By the 1900s, the scientific community’s understanding of race was both essentialist-defining each race by certain biological and social characteristics-and taxonomic (hierarchical). Scientists were struggling with the concept of race in divergent ways. Ales Hrdlicka and Earnest Hooten, two prominent physical anthropologists also trained as physicians, were influential at a time when the field focused mostly on anatomy and physiological variation.

Charles Davenport earned a Ph.D. in biology in 1892 from Harvard, and later became an instructor of zoology there. As a biologist, he pioneered the development of quantitative standards of taxonomy. A follower of the biometric approach to evolution which had been developed by Francis Galton and Karl Pearson, Davenport was also on the editorial committee of Pearson’s journal, Biometrika. After Mendel’s laws of heredity were “rediscovered”, Davenport became a strict convert to the Mendelian school of genetics. His 1911 book, Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, was a major work in the history of eugenics. Along with an assistant, Davenport also studied the question of miscegenation, or, as he put it, “race crossing” in humans. In 1929, he published Race Crossing in Jamaica, which purported to give statistical evidence about the dangers of miscegenation between blacks and whites.

- In 1911, a starving and nearly naked Indian man took shelter in a northern California slaughterhouse. He was turned over to anthropologist Thomas T. Waterman, who brought him to live at the University of California’s anthropology museum. He was given the name Ishi, which meant “man” in his native language. Most of the members of Ishi’s tribe, the Yahi-Yana, had been massacred during the California Gold Rush. Dubbed “the last wild man in America,” he became a popular attraction, and in his first six months at the museum, 24,000 visitors watched him demonstrate arrow-making and firebuilding. Ishi lived at the museum until he died of tuberculosis in 1916.

- The American Journal of Physical Anthropology was founded by Ales Hrdlicka in 1918, and he remained editor of the publication until his death. Hrdlicka also helped found the American Association of Physical Anthropologists in 1929, and from 1898 to 1925 was involved in anthropological investigations throughout the world. He was famous for his work on anthropometry, early man and human evolution, and in particular for his theory of migration of Native

Americans in Siberia and Alaska. - Earnest Albert Hooton was a physical anthropologist known for his work on racial classification and his popular books, including Up From The Apes, in which he described the morphological characteristics of different ‘primary races’ and various ‘subtypes.’ At Oxford he studied with R.R. Marrett. He was hired by Harvard University, where he taught until his death in 1954. While at Harvard, he was also Curator of Somatology at the Peabody Museum for Archaeology and Ethnology in Boston. Hooton was also instrumental in promulgating the constitutional approach to human biology, which theorized a correlation between physique, temperament and race.

Related Posts

Credit: National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution (BAEGN04815)

“The real problem of the American Negro lies in his brain, and it would seem, therefore, that this organ above all others would have received scientific attention.”

– Ales Hrdlicka

Perhaps the most influential American physical anthropologist of his day, Ales Hrdlicka was responsible for the direction of natural history museums in the U.S. Born in what is now the Czech Republic, Hrdlicka received his medical education in the U.S. He practiced medicine only for a short while, after which, in 1903 he began to organize the division of physical anthropology at the U.S. National Museum-what became the Smithsonian Institution-in Washington, and was its curator from 1910 to 1942. At the Smithsonian, Hrdlicka amassed one of the largest collections of human bones in the world. Although he conducted anthropological research on various groups, including black and white children, and juvenile inmates from New York asylums, his research focused mostly on Native Americans. The above quote was excerpted from the Committee on the Negro findings published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in 1926.