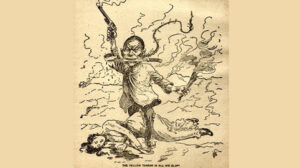

Source: Wikipedia, public domain image of 1899 editorial cartoon

When President Rutherford B. Hayes signed the Chinese Exclusion Treaty in 1880, he effectively reversed the open-door policy set in 1868 and placed strict limits on the number of Chinese immigrants allowed into the U.S. as well as on the number allowed to become naturalized citizens. Congress then enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, prohibiting for ten years both immigrationthe act of entering a country of which one is not a native to become... More from China and the naturalization of Chinese immigrants already in the U.S.

In the 1890 censusAn official count of a population and collection of demographic data. The United States Census... More, Chinese and Japanese racial categories were added. Two years later, the Chinese Exclusion Act was extended for an additional ten years by Congress, which also added a requirement that all Chinese workers in the United States register or face deportation.

Proportions of the 1890 census data were used as the basis for restrictive immigrationthe act of entering a country of which one is not a native to become... More policies in the 1920s.

- In the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated, or “separate but equal,” public facilities were legal.

- In 1898, the Spanish American War began when the USS Maine, stationed off the coast of Cuba, sank after a mysterious explosion. In Cuba and the Philippines, America helped defeat the Spanish, adding Cuba and Puerto Rico to its territories, and annexing the Philippines, Samoa, Guam, Wake Island and Hawaii.

- As a result of the Spanish American War in 1898, Puerto Ricans and other Caribbean island natives (Cubans, Dominicans), and Filipinos were added to the US population.

- The San Francisco school board ordered the segregation of Asian children in the city’s public schools in 1906, setting off an international crisis when Japan protested that such discriminationpolicies and practices that harm and disadvantage a group and its members. More violated its treaty relationships with the United States.

Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, copyright by Napoleon Sarony, New York City,

1890

“Our Constitution is color blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among its citizens”

– Justice John Harlan, from Plessy V. Ferguson decision

The 1896 case of Plessy v. Ferguson involved a Louisiana law requiring whites and blacks to ride in separate railroad cars; in its decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the law did not violate the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. The Court concluded that public facilities could be segregated based on race, codifying the “separate but equal” doctrine. Writing for the majority, Justice Brown wrote that the law did not “stamp the colored race with a badge of inferiority” and that any such suggestion is “solely because the colored race chooses to place that construction on it.’ In his dissent, Justice John Harlan argued, “Our Constitution is color blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among its citizens.”