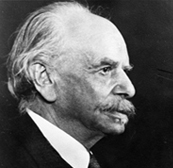

Credit: Ohio State University Archives

In the late nineteenth century, John Wesley Powell led the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution, which dominated the field of anthropologyThe study of humans and their cultures, both past and present. The field of anthropology... More in the U.S. at the time. Powell and his curator for ethnology, Otis T. Mason, v proponents of Lewis Morgan’s theory of cultural evolution-the idea that the social progress of a cultureThe full range of shared, learned, patterned behaviors, values, meanings, beliefs, ways of perceiving, systems... More is inextricably linked to technological progress. Franz Boas, often considered the father of American anthropology, opposed Morgan’s theory and introduced new ideas about the evolutionthe transformation of a species of organic life over long periods of time (macroevolution) or... More of cultures, as well as organization and classificationThe ordering of items into groups on the basis of shared attributes. Classifications are cultural... More of artifacts.

- Appointed to Columbia University’s anthropologyThe study of humans and their cultures, both past and present. The field of anthropology... More faculty in 1896, Franz Boas later rose in rank to consolidate and lead Columbia’s anthropology department, and is credited with creating the first Ph.D program in anthropology in the U.S. Boas played a pivotal role in forming the American Anthropological Association and promoting the “four field” concept of anthropology that includes physical anthropologythe study of the non-cultural, or biological, aspects of humans and our fossil ancestors. Physical... More, linguisticsthe comparative study of the function, structure, and history of languages and the communication process... More, archaeologyThe subfield of anthropology that focuses on cultural variation and power relations in past populations... More and cultural anthropologyThe subfield of anthropology that focuses on describing and understanding human cultures, including human cultural... More. He established that all societies’ biological characteristics, language, material and symbolic cultureThe full range of shared, learned, patterned behaviors, values, meanings, beliefs, ways of perceiving, systems... More are autonomous areas of anthropology, and that each is equally important to human nature, and that none is subordinate to another.

- In 1928, Margaret Mead published Coming of Age in Samoa. As Mead and her advisor Boas expected, the book upset many Americans and Western Europeans when it first appeared. Another influential book by Mead that became a cornerstone of the women’s movement was Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies, which claimed that females were dominant in the Tchambuli tribe of Papua New Guinea.

- In 1934, Ruth Benedict published Patterns of Culture, in which she contrasted the unique characteristics and personality traits of various cultures. A student of Boas, Benedict emphasized cultural relativism, in which customs and values are viewed within the context of the entire culture. The U.S. government consulted Benedict during World War II for an understanding of Japanese culture, and she helped President Franklin D. Roosevelt understand the importance of continuing the reign of the Emperor of Japan as the surrender offer was crafted. Her 1946 book, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, based on her study of Japanese society and culture, was later questioned by some who felt her work was shallow because her research had been conducted from a distance, rather than directly.

- African American anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston began her studies at Howard University before transferring to Barnard College where she received her B.A. in anthropology in 1928. Also a student of Boas, she is perhaps best known for her ethnographic research and writing based on African American folklore in Mules and Men (1935) and her novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

- William Montague Cobb was the first African-American physical anthropologist. He earned a medical degree from Howard University in 1929. He studied at Case Western Reserve under physical anthropologist T. Wingate Todd, whose progressive ideas opposed prevailing theories of racial determinism espoused by physical anthropologists Ales Hrdlicka and Earnest Hooton. Cobb was known for his research on human cranio-facial union at the Hamann-Todd Collection and the Smithsonian, and his works The Cranio-Facial Union and the Maxillary Tuber in Mammals (1943), and Cranio-Facial Union in Man (1940).

- British-born anthropologist Ashley Montagu was among the first scientists to argue against the concept of race. A student of both Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict, Montagu studied the procreative beliefs of the native tribes of Australia in the late 1930s. He taught anatomy at various schools in the U.S. and became a professor of anthropology at Rutgers from 1949 to 1955. He earned fame in the 1940s by arguing that race was a social construct, a product of perceptions, rather than a biological fact, and he was a principal drafter of the U.N. “Statement on Race” in 1949 that incorporated these ideas. Montagu vocally opposed anthropologist Carleton Coon’s notion that whites and blacks evolved along separate paths, and published in 1942 Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race. In 1950, Montagu authored the UNESCO Statement on Race. His varied interests were reflected in the more than 60 published titles including, The Natural Superiority of Women (1953), in which he argued that women were i many ways biologically superior to men, and The Elephant Man (1971), an account of John Merrick, the severely disfigured man of Victorian England which became the basis for the Broadway play and movie.

Related Posts

Credit: American Anthropological Association

“..there is nothing at all that could be interpreted as suggesting any material difference in the mental capacity of the bulk of the Negro population as compared with the bulk of the White population.”

– Franz Boas, from his 1938 edition of The Mind of Primitive Man

Often considered the father of American anthropology, Franz Boas led the department of anthropology at Columbia University and played a pivotal role in forming the American Anthropological Association. His approach emphasized the “four field” concept of anthropology that includes physical anthropology, linguistics, archaeology and cultural anthropology. Among his greatest legacies is his mentorship of women in the field of anthropology, among them Ruth Benedict, Margaret Mead and Zora Neale Hurston.