Credit: The New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture/Photographs and Prints

Division. (W.L. Champney & J.H. Bufford, 1770)

While American colonists waged war against the British, some patriots recognized the irony of their struggle for independence amid widespread slavery. “To contend for liberty,” wrote John Jay, one of the founding fathers, “and to deny that blessing to others involves an inconsistency not to be excused.”

During the Revolutionary War, the British actively recruited slaves–among them, those who belonged to George Washington. Virginia’s royal governor, Lord Dunmore, proclaimed that all slaves willing to bear arms for Britain would be granted their freedom. Slaves deserted in droves, and those who fought for Dunmore wore “liberty to slaves” emblazoned on their coats. When Washington took command of the Continental army in 1775, he initially banned the recruitment of black soldiers despite the fact that they had fought at Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill. Indeed, one of the first casualties of the American Revolution was Crispus Attucks, a runaway slave who was killed in the Boston Massacre in 1770.

- The Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776, and established independence from England.

- The U.S. Constitution was drafted in 1787.

- In 1777, Vermont became the first colony to abolish slavery.

- After the war, a group of slaves, a created a “maroon” colony, constructing a protected village of several houses and planting rice fields in a clearing near the Savannah River. The term “maroons” came from the Spanish word cimarrones, a term for runaway slaves. The maroons formed a band of black guerrilla fighters calling themselves “the King of England’s Soldiers.” By 1787, the maroons posed a serious threat-having attacked plantations and troops-so that the Georgia legislature sent its militia to destroy their village. Although the mission was successful, killing and wounding some maroons, many escaped to the South Carolina swamps. James Jackson, commander of the Georgia militia, urged the governors of South Carolina and Georgia to pursue the attack, and following a major raid, the maroon leader was captured, tried, and hanged; his head was severed and placed on a pole as a brutal warning to his followers. Many instances of attacks by maroons continued to be reported, however.

- In 1790, Congress passed an act requiring a two-year residency period before immigrants could qualify for U.S. citizenship to limit immigration from the British Isles, but more importantly it limited naturalization to European immigrants. Five years later, the residency requirement was raised to five years. In 1798, Congress passed four laws collectively called the Alien and Sedition Acts. One of these laws, the Naturalization Act, increased the residency requirement again, this time to 14 years. The Naturalization Act was eventually repealed in 1802, and the Alien Act expired in 1800, thereby making citizenship easier for European immigrants from Ireland, Scotland and Germany to enter the U.S.

- 1790 marked the first U.S. Census; the first racial categories included European, Native Indian, and African. The first census was created to count adult, white males who could vote, hold office, own property, pay taxes and become military recruits.

- The constitutional passage establishing the first census stated that the count in each state “shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three-fifths of all other Persons.” Slaves, the “all other persons” referred to were counted as 3/5th of a person in determining the population size of each state.

- The Fugitive Slave Law, which provided for the capture and return of runaway slaves who crossed state lines or escaped into federal territory, was passed in 1793. The law enforced Article IV, Section 2, of the U.S. Constitution, which authorized any federal district or circuit court judge, or any state magistrate, to decide without a jury trial the status of a runaway slave. Despite strong opposition in the North, where some states enacted personal-liberty laws to thwart the execution of the federal law, the state laws only ameliorated the law by allowing a jury trial for fugitives who appealed the decision. However, by 1810, opposition to the Fugitive Slave Law had become organized resistance to slavery, primarily through the Underground Railroad, which helped African slaves escape to freedom. A year later, Congress prohibited slave trade between the U.S. and foreign countries.

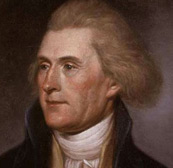

Courtesy: Independence National Historical Park Collection, Philadelphia.

Oil on canvas painted 1791 by Charles Wilson Peale.

…blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.”

– Thomas Jefferson, from Notes on the State of Virginia

In 1776, the Continental Congress voted to halt the slave trade, but their aim was to cripple the British economy, not emancipate African slaves. Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveholder who fathered children with his slave Sally Hemming, wrote a lengthy indictment of slavery, but the language was removed from the final version of the Declaration of Independence. However, in 1781, he observed in Notes on the State of Virginia, “I advance it therefore as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” Early scientific ideas about race were delineated by Jefferson’s notes.